Information externalities

A look at the negative impacts of increased information distribution and access. Also game theory.

Can more information make us collectively worse off?

For most of my life, I would have rejected a claim that more information is bad for society as ridiculous and authoritarian. However, modern society is weird. In particular, the internet is weird, and somehow, it appears that the forms of information dissemination that have emerged from the internet (news, twitter, social media) have not been universally good.

I recently took a break from social media and found that my life quality went up quite noticeably, and that I didn’t feel like I was missing out as much as I thought I would. This surprised me, because I was effectively restricting my information intake, and had concluded that this had a positive impact on my life.

There are the standard arguments for why information consumption is bad: it’s the sugar/fast food of our generation – we’ve evolved in information sparse settings and as such crave it at a primal level and are unable to healthily regulate our intake, modern sources are full of low-quality or misleading information that mislead you, it distracts you from the key things you should be focusing on, results in FOMO and commitment issues, etc etc.

Today I want to write a bit about information dissemination and why it can be bad. Of course, on the whole, I still believe that more information is good, and that the internet has and will continue to be net good for humanity. But it is also worth keeping track of its negative effects. Hopefully this inspires some intervention on your part, or at least is a fun read.

Networks and Braess’s paradox

In the 1900s, mathematician Dietrich Braess formalized an observation by economist Arthur Pigou that it is possible to construct a hypothetical city grid such that adding a road increases commute time for all residents (not just on average!). This became known as Braess’s paradox.

The setting is as follows: some number of citizens live in a city and commute from point A to B. They are self-interested actors and choose between several paths based on commute time. Commute time at any part of a road is a function of the number of other commuters on that road at that point in time.

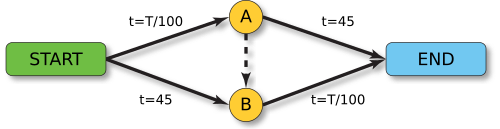

In the example below, there are four roads with commute time t specified as either constant or a linear function of the number of travelers T. Suppose there are 4000 commuters. If a and b commuters pick the top and bottom path respectively, the top path has commute time a/100 + 45 and the bottom has b/100 + 45. This is a stable system – people will switch from the top to bottom path or vice versa if there are more people taking the same route that they do in order to reduce congestion and minimize their commute time. This stabilizes at an equal commute time of 2000/100 + 45 = 65 minutes.

Suppose a road is added from point A to B with *0* commute time. Any person traveling on the top road, once they get to A, can either take the 45 minute top path or take the new road to the bottom path, where the remaining commute is T/100 + 2000/100 = T/100 + 20 minutes. People will keep switching until 2500 people take the detour, at which point the commute reaches an equilibrium of 65 minutes, but remember only 2000 people were taking the path through A to begin with.

However, during this time, the number of people taking the bottom right path will have increased to 2000+2000=4000, and the commute time has reached 85 minutes. The commuters through B will have caught on to what is happening, and will switch to the much faster top path through the detour. Through self-interested decision making, everyone ends up switching to this path, which converges to a commute of 4000/100*2 = 80 minutes, worse off than the original 65 minutes before the “instant shortcut” from A to B appeared. This is also stable – no one has any incentive to switch to another path, since the alternative routes take 85 minutes.

People who have studied game theory or economics will see what is happening: two of the four road sections have commute times that scale with the number of travelers, which means that commuting through them produces an externality. The detour from A to B encourages paths with higher externality, leading to a worse Nash equilibrium in the game of commuters picking paths.

Braess discovers Instagram

Jonathan Haidt has written extensively about the harms of social media, in particular on young teenagers. He makes a strong case for the internet being harmful through two mechanisms: addiction and externalities.

The addiction argument is well-understood – apps compete for attention, and do a pretty good job of it. However, the externality argument is more interesting in my opinion. Addiction is easy to argue against. It’s just plain bad and we should regulate apps to reduce addictive patterns such as infinite scrolling. The externalities on the other hand arise due to properties of social media that are intrinsically positive. We seek out information on what our peers are doing because it is useful information for us. The anxiety and FOMO produced by these apps are a consequence of a behavior we seek out for our own good.

As with Braess’s paradox, the introduction of social media has made possible new behaviors which on an individual basis are beneficial but which produce externalities that make everyone worse off:

The “road” in Braess’s paradox is, in the context of social media, the ability for people to selectively share information about their lives and to easily consume the information shared by their peers at a previously impractical scale.

The equivalent to the old road system was to focus on a smaller friend group, build reputation through face-to-face interactions, and figure out how you fit in within smaller communities.

The advantage of social media was clear – curating your social media presence became the most efficient way to scale your reputation, a form of personal marketing. Tracking your peers was important to stay up to date on events, trends, and social dynamics.

Reduced time spent offline in smaller groups was one of the externalities produced by social media, forcing those who were less reluctant to move to social media as well.

Over time, social status dynamics eventually stabilized. The new hierarchy might look different than it did before, but status is mostly zero-sum, so people traded their old lifestyles for a new one which, based on the evidence collected by Haidt and others, appears to have left everyone on average worse off.

The other externality which harms even those who were originally supportive of the move to social media is the highly manipulative nature of the information shared on these platforms – the number of people on the platform is larger, so the most successful and attractive people you see are going to outperform those you meet in real life. The information shared by people is skewed to look better than it is. The result is a reduction in self-esteem due to social comparison.

Of course, there are massive benefits to social media as well. Not everyone goes on these apps to signal and to compare themselves to others. However, if you find yourself mostly using these apps to share how awesome your life is and to compare your posts to your peers, it may be worth reflecting on what Braess would say and maybe taking a break.

Braess goes job hunting

The internet has also changed the market dynamics for employers and job hunters. Most companies today hire through digital platforms. As with social media, this affects how candidates present themselves to companies, and the way that companies look for people to hire.

In the world before the internet, cold outreach meant more. Finding a phone number and making a call, or writing a letter, or showing up at someone’s office was harder and rarer. It meant something, and was usually quite a positive signal for the candidate. The world was smaller, so companies were more likely to know the candidate, or at least had more time to assess them.

Today, there are are AI tools which lets candidates automatically apply to thousands of companies at once, while recruiters can send thousands of customized emails to candidates with minimal effort. Cold outreach works worse than ever. The exceptions are exceptions precisely because they don’t apply to the average candidate or company – you are uniquely talented, have particular expertise relevant to the company you’re applying to, you know someone already working there, or reach out to someone or some company which does not have a lot of inbound (sometimes for good reasons).

A few years ago, I found myself managing the recruiting pipeline for the startup I was working at. This was in the midst of the Covid-stimulus induced tech boom where every company desperately wanted to grow and talent was hard to come by. Nevertheless, we put up a single job posting and in a day had hundreds of applicants. After a week it was over a thousand. We did no advertising, did not post it on any college hiring platforms, nor nothing else to justify this level of attention. We were also not a particularly well-known startup at the time.

My original plan was to personally look through every resume and interview anyone who looked promising. That idea quickly went out the window. I ended up trying all the usual strategies you’d think of – delegating resume screening, filtering based on GPA or school, even having candidates complete an online coding assessment. I never ended up getting a chance to look through most applications.

My point being – in this new world where any candidate and company can blast out applications, it is impossible to consider every option. Pre-screening is unavoidable. The challenge becomes figuring out how to screen effectively. Many companies exclusively hire people they know to avoid this headache, for better or worse. Many use the signals we are familiar with – GPA, school, and previous experience.

These signals are effective because they are hard to fake. Candidates know that companies will ask for evidence if they get to the stage where they extend an offer, so exaggeration or lying doesn’t work. On the other side, candidates are far more likely to pick companies with established brands, even sacrificing salary, work-life balance, and more. They know that when they interview for their next job, future employers will have little time to assess how good of a job they did at the projects they were assigned, and as such are more likely to focus on their previous company and title.

If you already have the signals companies and candidates are looking for, this is great – you have more options than ever. If you don’t, you’re likely to find the job market more frustrating than it would have been in the past. The increased focus on signaling is a negative externality on society. It costs time and resources for people to acquire signals such as getting into a good college, doing extracurriculars, collecting publications, and preparing for job interviews. Some of this work is authentic and valuable, but a vast amount of effort and resources goes to waste every year on junk research, extracurriculars, and studying for tests and interviews that will never be useful.

Unlike social media, there is not an easy solution here. You can’t convince a few friends to delete their apps and touch grass. Companies need to hire, and it is good for social mobility and the world that they don’t exclusively consider people they already know. However, search and matching is a tough problem, and we currently don’t have good scaleable solutions. GPA, the school you went to, and previous job experience does correlate positively with job performance, and are hard to fake signals, and so will stick around for the foreseeable future.

The good news is that acquiring these signals usually requires you to learn or do something genuinely useful. Unfortunately, this is eroding. GPA inflation is commonplace, wealthy parents buy spots at top schools, and a single early internship at a good company through family connections can jumpstart a college student’s career. It is also a waste of talent – plenty of incredible people don’t bother or realize to pursue signaling credentials.

Overall, the U.S. is still better than other places in the world. For example, it is a common sentiment in east asian countries that your life trajectory is determined by the college you get into. Anecdotally, I’m also seeing a growing trend towards hiring through your network, which makes signaling less important and reputation (a much more robust and truthful signal) more valuable.

Nevertheless, across the board, we are seeing dissatisfaction with current digital platforms at a surprising scale. They provide enough value that they aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, though it’ll be interesting to see whether social media, dating apps, and networking platforms can continue to grow in the next couple of years. My read on this is that the current implementation of the internet solved some problems while creating others, and that a new and improved version will be necessary for people to transition over at a greater scale and permanence.

This is a topic that I need to revisit at Risk & Progress.

Indeed, the flood of algorithmically curated information, fed to our phones every minute of every day, is unique in human history. When combined with our biological attraction to negative news, our perception of the reality is altered in what I call the “reality distortion field.” :https://www.lianeon.org/p/progress-is-counterintuitive

I suppose my question is…what is the solution? If there is one? Do we regulate the algos?